On a recent Friday, as scores of people across Los Angeles prepared to go out drinking or stayed in to binge-watch their favorite TV shows, a small group of writers at The Last Bookstore explored the impact our parents’ lives, traits and behaviors have on us – for better or worse.

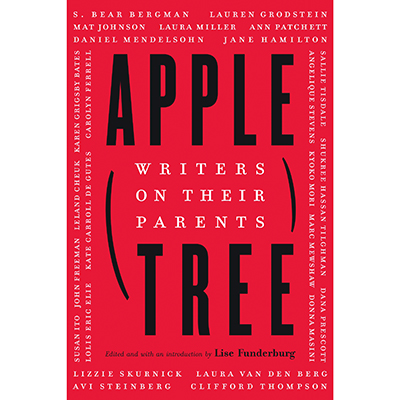

The event was a book launch for the anthology “Apple Tree: Writers on Their Parents,” a collection of essays edited by writer and University of Pennsylvania lecturer Lise Funderburg, who created this project after recognizing one of her father’s behaviors in herself.

We grow into adults by separating ourselves from our parents, but Funderburg, instead of recoiling from this echo of her father, wanted to know “what other inheritances” could be uncovered with some digging, and what meaning do they hold in terms of self-identity? Intrigued, she curated a group of writers to help her with this thesis. The 25 writers in the anthology include three L.A.-based writers: Karen Grigsby Bates, a correspondent for NPR’s Code Switch team; Shukree Hassan Tilghman, who has served as a writer and producer on the NBC series “This Is Us;” and Lolis Eric Elie, a journalist, food book author and TV writer (“Treme,” “The Man in the High Castle,” “Greenleaf”). In L.A. Parent’s January issue, Elie wrote about becoming a father for the first time.

Along with Funderberg, the L.A. writers read their heartwarming, tear- and laughter-inducing essays. In his essay “And Niriko Makes Four,” Elie examines the politics and passions he inherited from his late father, Lolis Edward Elie, who was an acclaimed civil rights attorney in New Orleans, as well as the wistfulness he feels over becoming a father for the first time after his father’s death. As Elie read, the youngest “apple” in his family tree, 1½-year-old Lolis Niriko, toddled in the audience to play with the promotional “Apple Tree” buttons lining the chairs.

Tilghman, in “Lies My Parents (Never But Maybe Should’ve) Told Me,” writes about the time he learned from his parents that Santa was a lie, among other unsettling truths. His mother shattered the Santa fantasy with love and a lesson about economics. A father now, Tilghman reflects: “Frankly, it seemed petty, my parents in a struggle for credit with a fictional character. Now that I’m a parent, I say, why should he? Parenting is hard. Scratching up money to pay bills and provide presents around Christmas time is hard. To hell with ol’ Saint Nick.”

In “The Feeding Gene,” Bates writes about the “near-pathological need” to feed people that runs in her family. She inherited it, too, happily cooking and serving everyone from her son’s college friends to eclectic mixes of friends and family during Thanksgiving. The feeding trait, she writes, will “continue in my family long after I’ve left the Earth.”

“Apple Tree” is a wonderful book to read over the holidays, as we slow down to spend more time with family – and maybe even open up to the idea of seeing through the eyes of our own children how much we mirror our parents.