The college admissions scandal that rocked several high-profile U.S. universities, nicknamed “Operation Varsity Blues,” ignited heated discussion in the academic community: Did parents believe their kids couldn’t handle the college admissions process on their own? Did the scandal reflect the parents’ driving desire to see their kids at a top-notch university? More importantly, was it front-page evidence of a larger, societal failing around building resilience in kids?

What is resilience?

Resilience ensures that children are equipped to handle life’s challenges, including the college admissions process, college life and beyond.

“Resilience is your ability to face a challenge and remain functional,” says Daniel Siegel, M.D., executive director of the Mindsight Institute, an educational organization based in Santa Monica that teaches how the mind, brain and relationships shape mental health and well-being. Flexibility and adaptability are terms sometimes used interchangeably with resilience, says Siegel, who is also the founding co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA.

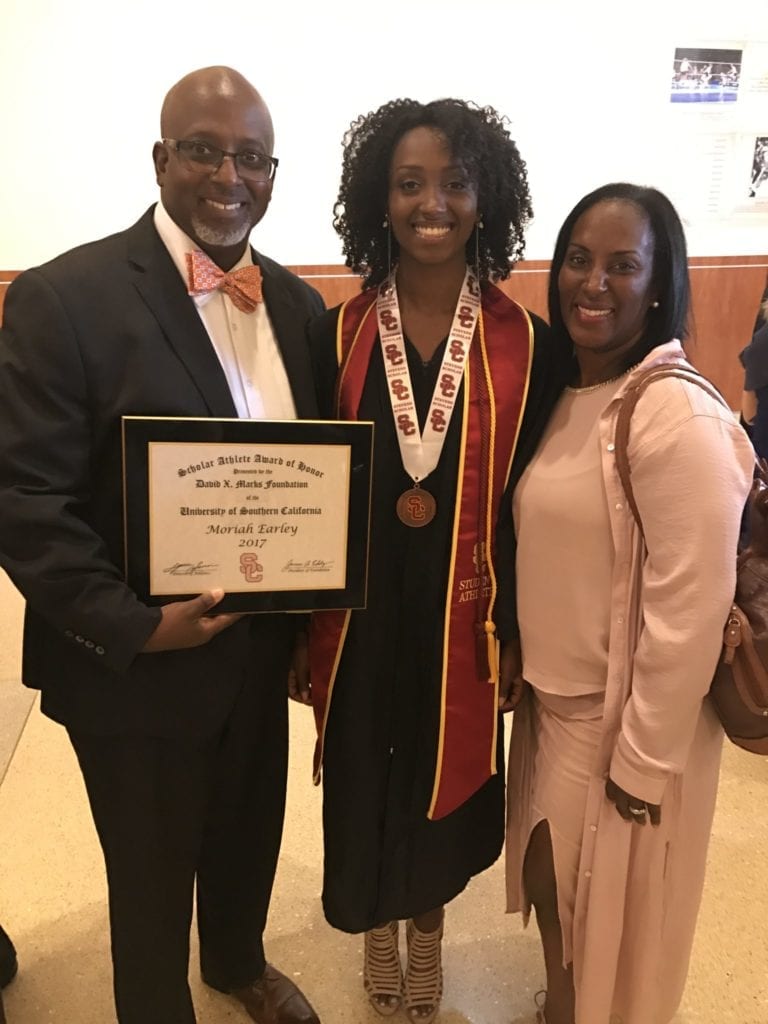

Resilience goes beyond just being able to get up when you’ve been knocked down. “I think resilience is more than that,” says Darin Earley, Ed.D., educational consultant and director of the Loyola Marymount University Family of Schools. “Resilience is not only that you get up when you’ve been knocked down or challenged. It’s when you get up and you’re better, you get up and you’re smarter.”

A veteran educator with 30 years of experience, Earley says that resilience isn’t a static force that helps kids survive. It’s a force that strengthens every time it’s engaged, kind of like walking. “Everybody has the potential to walk, unless you have some kind of physical disability, but there are some things that parents do along the way that may accelerate that process or impede it,” he says. “If you have a child and all you do is carry that child, and that child doesn’t get a chance to strengthen those legs, walking may come a little slower.”

Practicing resilience, then, is the key to developing it. It increases only by facing obstacles, and this should begin in early childhood.

Why is resilience important?

In many ways, resilience is the basis of well-being. “Resilience allows our children to learn how they can regulate their emotions, control their impulses and reflect on what’s going on,” says Siegel. “So, if you want your child to have well-being, you want them to have resilience.”

Siegel says kids who lack strong resilience typically display one of two responses to obstacles: rigidity or chaos. A child exhibiting a chaotic response would experience intrusive memory, emotional outbursts or screaming, for ex-ample. A child exhibiting a rigid response would shut down and disconnect. “So instead of flexible, they’re inflexible. Instead of coherent, they’re incoherent. Instead of energized, they’re deflated. Instead of stable, they’re unstable,” Siegel says. It’s common for children and teens to become rigid or chaotic temporarily, but the frequency and duration of this should decrease as they mature. A 14-year-old, for instance, shouldn’t think or behave like she did when she was 4.

How does resilience grow?

Resilience begins to develop as children learn first to differentiate between their minds, emotions and actions – and then to draw connections between them. To become highly resilient, children must develop “mindsight,” says Siegel, which is the ability to see the mind and talk about it.

Once children understand that their thoughts, feelings and memories are not the totality of who they are – that they are just aspects of how their mind is functioning in that moment – then the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which controls impulses, strengthens, according to Siegel. This essentially puts a pause between impulse and action, which builds resilience. So, kids who can talk about their minds and emotions and reflect on them are better able to develop secure identities, control their actions and cultivate resilience.

A non-resilient child who receives an F on a report card might internalize the F and yell, “I’m a failure!” A resilient child would recognize the emotion of disappointment, identify the thought I’m a failure, and then appropriately manage them. He would recognize that the thought is fleeting and then feel confident that he could take actionable steps to obtain a higher grade.

Resilience through relationships

Experts maintain that strong, supportive relationships are the emotional seedbeds that house resilience.

Daisy Gomez, Ed.D., a training specialist at the UCLA Prevention Training Center of Excellence, says consistent, stable relationships teach kids they will be supported through any obstacle, disappointment or failure. Knowing they have supporters in their corner through life’s difficul-ties – which can range from academic disappointments to divorce or the death of a loved one – nurtures self-efficacy and empowerment.

But support isn’t the only way parents and teachers can cultivate resilience in students. “Having resilience modeled by those around you gives you a clue into how to do it,” says Gomez, who trains school personnel throughout L.A. County. Because children often model their behavior after the adults in their support system, Gomez and Siegel stress the importance of parents and educators continuing to strengthen their own adaptability. “If we as adults are not checking our own resilience, then it can be a challenge to nourish and enhance it in others because we cannot give what we don’t have,” says Gomez.

RELATED: Understanding California Stated Standards for Education

Parents who regularly “sit inside” their own minds and can say, “bring it on” to every challenging emotion and experience, can teach their kids to do the same, Siegel says. Parental and school support systems

Earley says schools that help students develop strong habits of the mind through mastery grading increase students’ resilience. “Mastery grading builds resilience because [it] says, ‘I’m going to have to do this until I get it right. It’s not just about me getting a grade that I’m cool with,’” he says. “Mastery grading says, ‘I’ve got to keep tweaking it and doing these little changes – sharpening my academic saw – until I get it.’” This practice, coupled with open-ended, critical-thinking questions, helps students push through difficulties until they discover a solution, which fosters experimentation, creativity and a sense of accomplishment.

Parents can give their children open-ended critical-thinking opportunities that test mastery as well, even if their child’s school operates using a traditional letter grading system. If a child receives an A or B on an algebra test, Earley says parents can ask their children to prove that they understand a concept such as linear equations “beyond the test” by saying, “I want you to think about ways that you could prove to me that you understand linear equations without me designing a test for you.”

The challenge will compel the child to ask clarifying questions, think outside the box and think critically not just about what she knows, but how she can best communicate it. Earley says that by the end of the exercise, she will realize, “Hmm, I have the capacity to do some things I didn’t think I could.”

That’s resilience.

A child who brings home a C or a D on that same test can also be coached on resilience and mastery, says Gomez, but only after parents have evaluated their expectations. Parents and students, she maintains, can experience different internal and external outcomes if parents simply shift their expectations to appreciation. If parents don’t expect straight A’s, when their child comes home with C’s, parents can celebrate their process by saying, “That’s awesome. I saw how hard you worked. I think that’s a great start and I know you have it in you to do better. So, you tell me what you need.”

This strengths-based approach engenders the confidence kids need to keep trying and to recognize they can persevere through any difficulty, including not getting into their first-choice college.

Navigating college admissions

Ultimately, students suffer when they are parented toward an outward achievement such as getting into Stanford. “If you just raise your child to get into a certain college, the child becomes invisible and they’re set up for failure,” Siegel says.

When a child is raised just to gain achievement, he feels like a complete failure if he doesn’t accomplish a goal, which can lead to a shattered sense of self and – in extreme cases – self-inflicted bodily harm. In essence, the child learns to function like a “human machine, not a human being,” says Siegel.

Gomez says a resilience-informed lens wonders, I didn’t get into ‘X school,’ but which other colleges offer similar pro-grams or experiences? A resilience-informed lens thinks, May-be I can attend community college for two years and transfer, or maybe I can take a gap year and build my resumé and re-apply.

When resilient kids run into a setback, to them it’s not a dead end; instead, it’s just a detour. “They look and say, ‘OK, I’ve got to turn left here because this wall’s here. I’m not quitting. I’ll find my way around it,’” says Earley.

The greatest gift a parent can give a child, according to Earley, isn’t admission into an Ivy League school, but rather the gift of a resilient mind that says, “This is not the end of me; this is just a setup for a comeback.”

Chanté Griffin is a writer living in Los Angeles whose work centers on race, faith, culture and education. You can follow her on Twitter @yougochante.