Fifth-grade teacher Leticia Citizen conducts a class discussion on America’s Jamestown settlement using Common Core strategies that integrate math and language-arts skills. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

In a fifth-grade classroom in Pasadena, students receive language arts and math instruction as part of a well-researched, artifact-driven social-studies lesson on Jamestown, VA. In the San Fernando Valley, third graders apply their math skills to figure out how many medium pizzas it would take to feed 72 people. And over in Santa Monica, fourth-grade students are taught to answer reading comprehension questions based solely on the evidence presented in the story. National Common Core Standards for education are now in full effect in California.

There have been critics of the standards, and bumps in the road in their implementation, but we found teachers, students and parents who give Common Core high marks.

In many California school districts, there have been big changes in the way English and math are taught. Gone are rote learning, strict reliance on textbooks and information presented out of context. The emphasis now is on critical thinking, collaborative learning, communication and creativity. “For me, it’s just good teaching,” says Frances Werking, an elementary curriculum coach for the Pasadena Unified School District. “You have a lot of collaboration. The kids are not just learning from the teacher, they’re learning from each other. Common Core is less about information retrieval and more about what you do with that information.”

Jefferson Elementary Principal Amin Oria checks comprehension of a social-studies lesson while Elementary Curriculum Coach Frances Werking looks on. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

In 2010, California became one of more than 43 states that adopted the Common Core State Standards for English and math. The Smarter Balanced Assessments, aligned to the standards and designed to measure progress in English and math for select grade levels, were required for the first time during the 2014-15 school year, with the first results released in September.

Common Core is designed to offer a single set of educational standards that help ensure that all students graduate from high school with the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in college, career and life.

In some school districts, such as Pasadena Unified, teachers and administrators have been preparing for the transition to Common Core for a few years.

In the Classroom

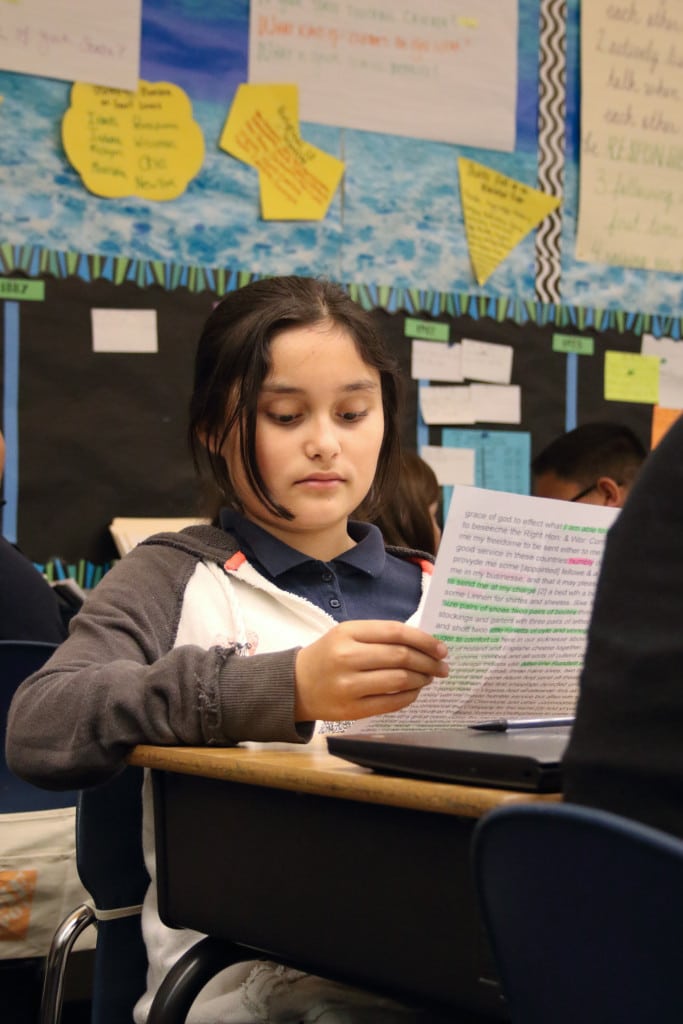

On a cloudy May afternoon at Jefferson Elementary in Pasadena, students in Leticia Citizen’s fifth-grade class learn language arts by reading a personal letter, dated 1622, which they locate online. Math is integrated into the lesson as students perform calculations based on a merchant ship’s manifest, which lists its cargo and passengers. Later in the week, the fifth graders are handed a graph that shows the number of English settlers engaged in various occupations in Jamestown. The students have to answer questions such as: “What information does this graph give me? How might the variety of occupations of the settlers affect the success and failures of the colony?” Citizen has several artifacts in the classroom that she brought back from a trip to Virginia. Students talk about their assignments in small groups, exchanging answers and information or collaborating on projects.

A Jefferson Elementary student uses critical-thinking skills to make sense of a 17th Century personal letter as part of a social-studies lesson. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

Margaret, a student in Citizen’s class, says this kind of instruction works for her. “I like it. It’s kind of easier [than before], not as rushed,” she says. Her classmate Shawn says he thinks that integrating the subjects makes a lot of sense. “It helps when it is put together,” he says. “Every subject has to do with each other.”

At Grant Elementary in Santa Monica, fourth-grade teacher Rachel Mauck is busy helping students with their language arts assignment one June afternoon. Because of the shift to Common Core, Mauck’s students are now required to conduct extensive research before submitting assignments. “We’re asking them to question: Is this a reliable source? We’re asking them to look at two or three sources,” she says.

At Vena Avenue Elementary in Arleta, third-grade teacher Mayra Aguinaga shouts out, “Five, four, three, two, eyes on you!” to get her high-ability students’ attention. It’s a fun way of signaling that their daily math lesson is about to begin. Today, the assignment is to figure out how many eight-slice pizzas would be needed to feed three classes of 24 students. After allowing the kids to collaborate for a few minutes, Aguinaga invites three to the front of the room to explain their answers with words and pictures.

“So, what I did to find out what 24 times three was, was to split 24 in half,” begins Andrew, one of the students at the whiteboard. Aguinaga facilitates the discussion by praising students’ choice of strategies or by reminding the kids of rules they might have forgotten to use. For 8-year-old Amanda, a classmate of Andrew’s, the mixture of class discussions and exercises with traditional textbooks keeps her engaged. “Math is my favorite subject,” she says. “With the book, I get to learn even more things and get to have even more fun.”

At Roosevelt Elementary in Santa Monica, second-grade teacher Stefanie Mathewson circulates among her students every morning as they deconstruct numbers and use math in a practical manner. On this day, students given the number of minutes a boy spent on the beach, and the number of those minutes he spent relaxing, are trying to figure out how many minutes the boy walked on the beach. Later, they are asked to convert the minutes to hours. Two or more students present their strategies, while the whole class participates in a compare-and-contrast exercise.

How It’s Different

Veteran Santa Monica-Malibu Unified district teacher Stephanie Mathewson employs group questioning strategies to guide second graders in converting minutes to hours. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

Mathewson says one of the biggest changes Common Core has brought to education is the focus on student collaboration. “There’s a lot more time spent having students talk to each other, analyzing each other’s work, talking about strategies,” she says, pointing out that this is precisely what students will have to do in college and in the workplace. “They need to communicate ideas and analyze ideas with others.”

Aguinaga says that she now spends more time teaching concepts than she did before Common Core was implemented, and that emphasizing the basics helps her students problem-solve more quickly. “Language arts is [now] more analytical and evidence based,” she adds. “It’s about really breaking down the text looking for specific features like author traits and vocabulary.” At many schools, this is done with the help of graphic organizers and other tools. “It’s really good for the students when they get to the upper grades,” Aguinaga explains.

She and other teachers also say Common Core gives students more latitude to solve problems.

While Common Core is resonating with a lot of people, it is not without its challenges. Few textbooks are aligned with these new standards, so locating the right resources to create meaningful lessons can be time consuming. Yet for many teachers, it is worth the effort. “I need to find ways to make it interesting and to be sure they are getting the skills they need and still be engaged,” Aguinaga says. “I like it when I can say, ‘Wow! You really made that analysis.’”

Making It Work

Vena Avenue third-grade teacher Mayra Aguinaga listens as a student explains how she figured out how many pizzas to buy for three classes of 24 students. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

Vena Avenue Elementary Principal Maria Nichols says her school is committed to making Common Core work in the classroom. Instructors at the school meet on a regular basis to design grade-level lesson plans that are in alignment with the standards. “Planning is 70 percent of your success,” says Nichols. But she adds that it takes strong leadership to make sure teachers are prepared. “Principals have to build a structure and a system that will allow for teachers to plan in this collaborative, professional way.”

Parents are also an important part of the Common Core equation at many schools, which put out flyers and even conduct workshops to keep them informed. Shabazza Higiro is one parent who is pleased with what she sees. Higiro’s daughter Malia is in Mauck’s class at Grant Elementary. Higiro also has a teen-age daughter, and so has seen the difference in teaching styles over the past few years. “Before, there was more rote memory, students worked alone and were shown only one way to understand things,” she says. “Now there is more group work and there are multiple ways of getting a solution to a problem. It shows that they are learning, and the process of that learning.”

Two second-grade students use collaborative learning to figure out a math problem at Roosevelt Elementary in Santa Monica. PHOTO BY TALIA DEKEL

Higiro says she sees Malia using math, science and other skills in everyday life. “I see her relating science and math to cooking or when we are driving,” she says.

Malia says she is excited about coming to class each day and using hands-on educational tools such as models to learn subjects like math. “It’s interesting,” she says. “It’s an easy visual and is helping me to understand why. It’s good because there is more you have to do to complete the problem.”

Sara Tropea volunteers at Grant Elementary once a week, and her daughter, Scarlett, is Malia’s classmate. “It’s amazing,” she says of Common Core. “[My daughter’s] depth of thinking is profoundly different than it was in the past. The students are thinking deeply on topics that I was not learning in the fourth grade.”

Besides the academic importance of Common Core, Higiro and Tropea believe the collaborative learning and deeper thinking it encourages will ultimately have broader implications for society. Higiro is looking forward to social change as a result of student collaboration. “It could lead to better understanding when people from different perspectives work together,” she says.

Tropea agrees and says she thinks Common Core has the potential to create a new generation of leaders. “I think they are going to do a heck of a better job than we have done,” she says. “I’m hopeful.”

Saida Pagan has worked as a local television reporter and producer, as well as a freelance writer.