Avremel Mayer, who has Down syndrome, lives in a group home run by ETTA Center, and now helps teach life skills to other adults with special needs. PHOTO COURTESY ETTA CENTER

Avremel Mayer has Down syndrome – and an independent streak. When he was a teenager, a yellow school bus picked him up each morning for the trip to Fairfax High. He had convinced his parents to let him wait for the bus on his own.

One day, he decided the school bus was coming too late. “He walked to the corner, picked up the [city] bus to Fairfax Avenue and told the driver that he wanted to go to Fairfax High,” says Avremel’s father, David. “The bus driver told him the number [of the next bus to take], and after that, he was taking it every morning.” His parents didn’t find this out until an aide at the school told them how terrific it was that Avremel was taking public transportation on his own.

“He’s pleasantly surprised us in every aspect of his life,” says David of his son, who is now 30, lives in a group home and has a job helping the activities director at an assisted-living facility. But that doesn’t mean the Mayer family didn’t plan for Avremel’s transition to adulthood.

If you are the parent of a child with special needs, you should be planning, too.

You Can’t Start Too Early

Parents can start building the skills their kids will need from an early age. Teach your child simple living skills such as making the bed with what Lela Rondeau, coordinator of the LAUSD Office of Transition Services, calls a “backward plan.” Make the bed almost all the way, then have your child do the last step. Next time, leave two steps for your child to finish, and continue this way until he or she is making the bed completely. At the grocery store, give your child responsibility for gathering one or two items on the list, or pay in cash and ask your child to count the change.

The key is to work these exercises into your daily routine. “Any area where we can build independence for a child is a win,” Rondeau says.

AbilityFirst is one of many programs in the area that helps young adults with special needs learn job skills. PHOTO COURTESY ABILITY FIRST

And if your child has behavior problems, tackle those now. They might not seem like a big deal if your child is 4 or 5 years old, but no one wants an adult employee who routinely melts down or throws tantrums. “No employer’s going to take a child in unless that behavior is under control,” says Wayne Fogelsong, principal of the Miller Career and Transition Center, which provides employment-based training for LAUSD students ages 18-22 with special needs.

Explore Your Options

Schools have a host of services available for kids with special needs, and it’s worth your while – beginning when your child is in the early elementary grades – to find out what your district offers. But when you do secure services for your child, make sure that building independence is part of the goal.

“With any service within special education, the intention should be temporary,” says Rondeau, because that service might not be available once a child finishes school. A one-on-one aide might help keep a child on task during class, but it isn’t feasible for an adult to have a one-on-one assistant throughout life. Rondeau advises parents to ask, “How can I use this service to build my child’s independence?” Can that aide teach strategies that will help the child stay focused without help?

Beyond school, parents of children with special needs can be one of the best sources of information about programs and services. “Find out what they know,” suggests Keri Castaneda, chief program officer at AbilityFirst, which provides employment, recreational, socialization and housing programs for children and adults with special needs.

Castaneda also reminds parents to stay connected – at least once a year – with their Regional Center, even though they might be accessing most of their child’s services through school. Eventually, your child will finish school and receive services through the Regional Center instead.

Make Sure Transition Is Part of the IEP/IPP

Farming is one of many vocational programs offered to students with special needs through LAUSD’s Miller Career and Transition Center. PHOTO COURTESY MILLER CAREER AND TRANSITION CENTER

By the time your child is 16, a transition plan that addresses education, employment and independent living should be part of his or her Individualized Education Program. Transition services are federally mandated for these students.

Bringing your teen to their IEP meetings is also a good way to build independence and self-advocacy. As long as the disability is talked about openly and in a non-shameful way, attending meetings can help teens learn about their disability, talk about it with others and advocate for themselves. If your child can tell a potential employer, “I have autism, and I need a visual chart to help me learn routines,” that could be the key to success.

LAUSD is trying to get kids into their IEP meetings earlier, and promotes student-led IEP meetings, “just to have them start to take the ownership,” Rondeau says.

Learn About Your Child’s Interests

As an adult, your child might want to participate in a social-recreation program, volunteer, hold a full-time or part-time job, or some combination of these things. To find the right fit, start learning as much as you can about your child’s interests by getting out there and exploring together.

Rondeau recommends having kids join clubs at school, and taking advantage of volunteer opportunities at hospitals, animal shelters, senior centers and other organizations.

If you think your child might be interested in post-secondary education, visit your local community college together. And to learn about a host of jobs and the skills they require, check out the ONETonline.org website, a searchable occupation database.

Regional Center vendor fairs are a great place to find out about day programs, employment options and social recreation programs. You can visit the programs themselves with your teen, to see what might be a good fit.

Yudi Bennett discovered that her son Noah, who has autism, was talented with computers and passionate about art. In 2011, she came together with other parents of kids on the spectrum to found Exceptional Minds, a vocational school in Sherman Oaks that trains young adults with autism to work in the film, television and gaming industries. Her son, now 20, eventually attained professional certification in programs that allow him to work in the movie industry.

“Research the opportunities that are out there and try a lot of different things,” Bennett advises parents of children with special needs. She involved her son in a number of different programs, traveled with him, and did everything she could to make opportunities available. “Allow yourself time to discover who your child is,” she urges.

Choose a High School Track

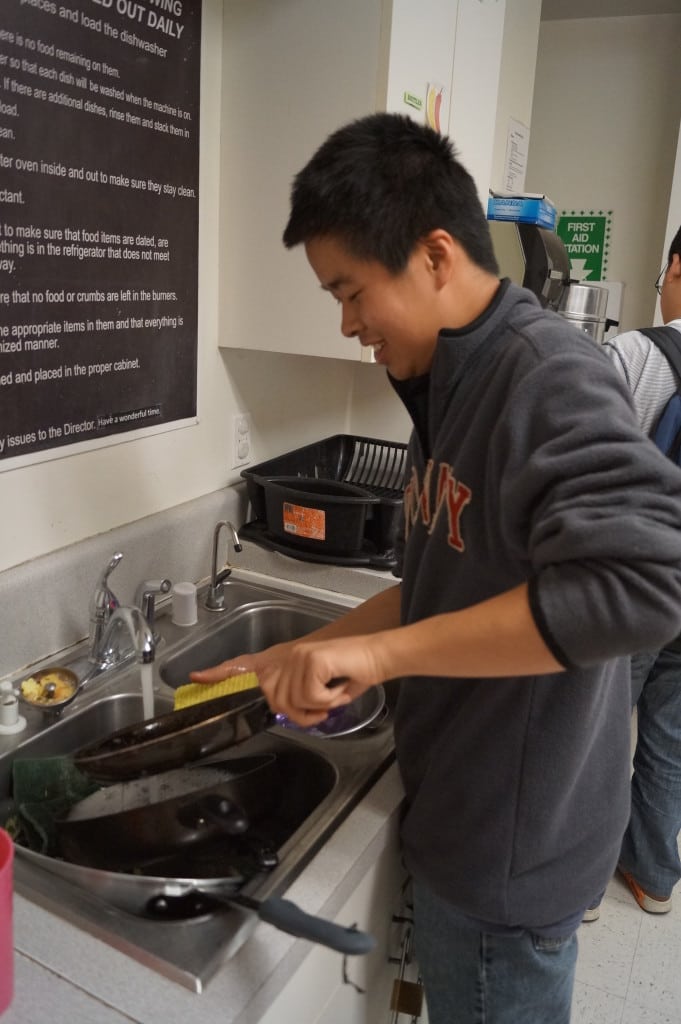

At AbilityFirst, teens and young adults learn life skills, including housekeeping tasks. PHOTO COURTESY ABILITY FIRST

Once your child enters high school, she or he will be placed on either a “diploma” track or a “completion” track. This means that students either earn a diploma by meeting the school’s traditional requirements, or get a certificate of completion by meeting credits, attendance and/or IEP goals.

Fogelsong advises parents to choose a track carefully, because graduating with a diploma won’t necessarily guarantee that a student has the skills to land and keep a job.

Students who forego the diploma, on the other hand, can stay in school until age 22 and participate in programs such as those at Miller Career and Transition Center, which build job skills. Fogelsong says parents often struggle with this. “The issue really comes down to parents realizing what they want for the future of their student,” he says. “This is a dilemma. We’re always hoping that the parents are looking through the eyes of their child.”

At Miller, students spend three years participating in work programs that include auto detailing, culinary arts, graphic arts, clerical skills, furniture repair, construction, landscaping, textiles and theater arts. The program collects data from each of these jobs, and generates a report of each student’s job skills and strengths. After participating in three of these programs over three years, students spend their fourth year at work in the community. “We’ve gotten numerous kids hired as a result of that,” Fogelsong says.

What Happens After High School?

Finishing high school is a big transition. Along with that, parents of children with special needs should be prepared for another. “Their son or daughter is going to be moved from their case worker at the Regional Center who is assigned to children, to an adult case worker,” says Michael Held, Ph.D.

Held, executive director of the ETTA Center, which assists people with special needs and their families, says parents often are not ready for this. This trusted relationship, and everything they had learned about how to secure services for their child, changes at once. “You have to learn a new language, and that can be shocking and startling for parents,” Held says.

Parents whose children want to go on to college experience another paradigm shift. Because while elementary and high schools are obligated by law to seek out and provide services for children with special needs, colleges and universities are not. Regional Centers – and post-secondary schools themselves – often provide support services, including assistance with applications, class scheduling and study skills, but students have to actively seek them out, according to Rondeau.

Ready For a Job?

Exceptional Minds, a program that trains teens and young adults with autism to work in the motion picture, television and gaming industries, was started by a group of parents who wanted to help their children find employment. PHOTO COURTESY EXCEPTIONAL MINDS

Whatever path they take to get there, paying jobs, often called “competitive employment,” are now considered the first, best option for many young adults with special needs. “Work is about self-esteem and quality of life. It opens up your world in a lot of ways,” says Bennett, noting that many people meet most of their friends, and even their spouses, through work.

That doesn’t mean finding a job will be easy. “I’ve seen so many young adults develop improved communication skills, improved life skills and become contributing members through a vocational outlet,” says Held. But he describes the job prospects for these adults as dismal. “Society hasn’t embraced the idea of meaningful employment for people with special needs,” says Held. “Parents really have to be aggressive and proactive in looking for opportunities.”

That’s just what Bennett did in creating Exceptional Minds, which offers employment opportunities as well as teaching job skills. From their first graduating class of eight students, the organization has placed one graduate at Stargate Studios (creators of “The Walking Dead”), and employs five others in the Exceptional Minds studio doing visual effects clean-up work, end credits and other work on films and in television. “This is life-changing for these guys,” says Bennet. “They go to the theater and they see shots they worked on on the screen.”

Avremel Mayer’s first job experience was through an organization called Tierra del Sol. Based in Sunland, it provides educational and volunteer opportunities and job training to adults with special needs. Then, a few years ago, someone who had met Avremel as a child opened an assisted-living center for seniors. He knew Avremel was outgoing, thought he would do well working with older people, and offered him a job.

Autism advocate Joanne Lara, creator of the nonprofit Autism Movement Therapy, which provides dance therapy for people with autism and trains service providers, is working to create a program she is calling “Autism Works Now!”

Her goal is to build a database of young adults with autism and their skill sets, encouraging prospective employers to hire their participants on a temporary basis – and eventually as permanent employees. “They’re much more likely to give them a job once they see them at work,” Lara says. “Many times, our kids just don’t shine in an interview.”

Time To Move Out?

Paying jobs, otherwise known as “competitive employment,” are now considered the best option for many young adults with special needs. PHOTO COURTESY ABILITY FIRST

Like good jobs, housing options are scarce for people with special needs, many of whom want to leave home. “Housing is a big challenge,” says Held. “The sooner parents start on it, the better.”

Rent-subsidized housing is available through organizations such as United Cerebral Palsy, which runs 11 independent-living apartments in Southern California. AbilityFirst runs 10 apartment complexes, a “family-style” adult residential facility, and a residential home for seniors.

And there are group homes. Held says the options there are similar to comparing public school with private school. Some group homes are fully funded by the state, while others are privately run. Held puts the cost range for those at $1,000 to $10,000 per month. ETTA currently runs four group homes, primarily serving the Jewish community – including the home where Avremel Mayer lives with five other young men.

For Avremel, a group home had been part of the plan from the beginning. And a space opened up at ETTA just months after he finished high school. “It was very hard to let him go,” says his mom, Lynn. “I didn’t want him moving out at 23, but it was the best. It has been so positive.”

He has learned life skills including cooking, cleaning and how to do laundry, and now helps teach those skills to the other residents. “We have golf and movies and barbecues, and we have a great time,” Avremel says. He takes the Metro to his parents’ house to visit most weekends, but still has his independent streak. His next goal is to live in an apartment on his own.

For the Mayers, as for all parents, letting go is part of the process of seeing their son grow. “Parents have to come to recognize that they’re not going to outlive their children, and they have to prepare for that eventuality,” says David Mayer. “And if you smother the child, it’s going to be a disaster.”

Transition Resources

- AbilityFirst: abilityfirst.org, 877-768-4600

- ETTA Israel Center: etta.org, 818-985-3882

- Exceptional Minds: exceptionalmindsstudio.org, 818-387-8811

- LAUSD Office of Transition Services: achieve.lausd.net, 213-241-6701

- Miller Career and Transition Center: 818-885-1646

- Tierra del Sol: tierradelsol.org, 818-352-1419

- United Cerebral Palsy: www.ucp.org

Christina Elston is Editor of L.A. Parent