Long Beach native Elana K. Arnold was in middle school when she fell in love with her first fictional character — Anne of Green Gables.

The PBS miniseries adaptation of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s books premiered in 1985, and Arnold’s seventh-grade teacher assigned her students to watch it for homework. Because she was on punishment at home, Arnold watched the show on a tiny black-and-white portable TV that she snuck into her room, fiddling with the TV’s rabbit ears to get the picture as clear as she could, then melting into the story moving across the screen. And when she learned that the show was based on a book series, she became enraptured by the literary version, too.

“Anne was my idol,” Arnold says. “She understood what she wanted; she knew how to ask and advocate for it. Even before I met Anne, I wrote — poems, little stories, lots of beginnings.”

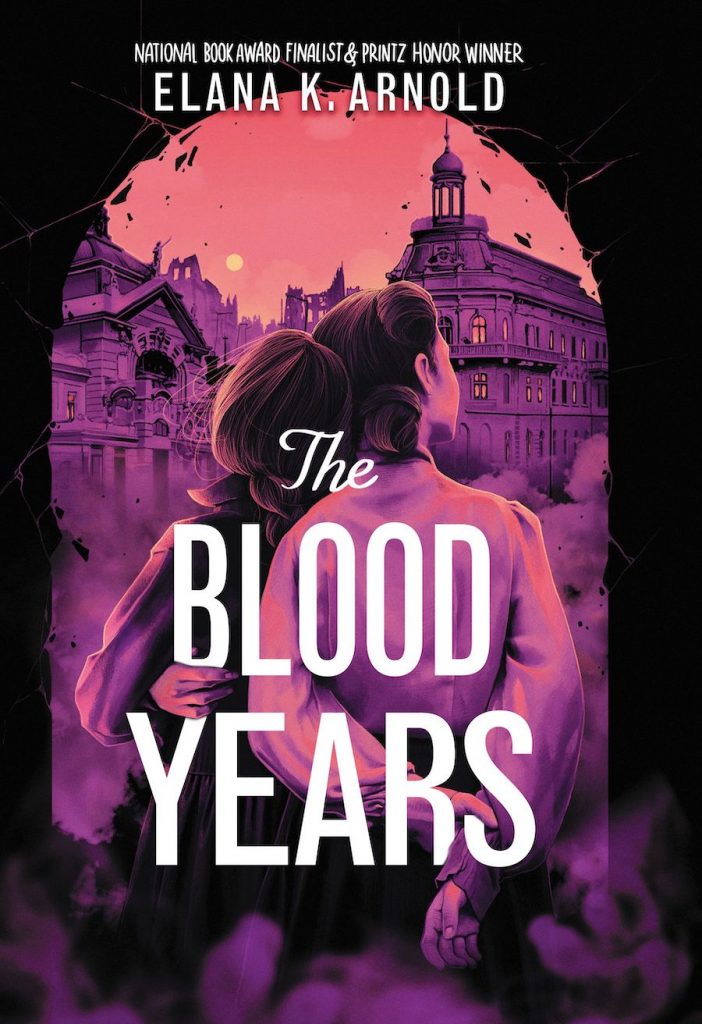

Arnold went on to become a prolific and bestselling author of books for children and teens, garnering awards and honors that include being named a finalist for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature and receiving the Michael L. Printz Award honor.

Arnold’s latest, “The Blood Years,” is a fictionalized version of her grandmother’s teenage years growing up during the holocaust in Czernowitz, Romania. The novel’s launch on Oct. 10, though, will look quite different from the launches of the author’s other books — namely because she finds herself caught in the book-banning frenzy that has swept the nation. At least 16 of Arnold’s YA and middle-grade books have been banned or challenged. On Oct. 22, she’ll serve on a Banned Books Week panel co-hosted by the Holocaust Museum of Los Angeles and PEN America Los Angeles, and on Oct. 26, she’ll be a panelist for a similar book censorship talk at UC Irvine, also co-hosted by PEN America L.A.

I spoke to her in the weeks leading up to her launch.

Book banning is not new. So many of our beloved authors — Judy Blume, Toni Morrison — were banned in years past. How would you compare what’s going on today to past censorship?

Today’s book banning fervor seems akin to other moral panics of the past: the Satanic Panic and the Dungeons & Dragons panic in the 1980s and 1990s, to name just two of the more recent panics. Everything is cyclical, as Opa, a character in my forthcoming novel, “The Blood Years,” often says. Panic is cyclical, too. The target shifts, but the urge to blame and scapegoat seems eternal. This time, books and their authors — especially books and authors that challenge heteronormative patriarchy and white supremacy — are at the center of the target.

Why do you write?

I write for lots of reasons. When I was young, I desperately wanted people to like me. I deeply yearned for friendship, and to be understood, and to understand others. But I didn’t have these things. What I didn’t know then is that many of my difficulties in social situations, much of my yearning to connect but inability to penetrate the circles of friendship of my peers, most of the reasons the other kids considered me “weird” were related to the fact that I’m autistic. As a child of the ’80’s and a girl, I was passed over as “gifted and talented” and “just quirky.” No one seemed to notice my deep loneliness, my constant state of confusion, my sense that I was walking around in a world fogged thick with clouds. Books were a place where I got to hear what the characters were thinking — what they feared, what they hoped, what they dreamed. I suppose music is a similar portal for some people, but as a noise-averse person, music wasn’t something I turned to. A quiet room, a bowl of fruit or chocolate, a snoring dog or purring cat close by, a book. Ahh.

Writing is a natural evolution of the relationship I’ve always had with books. It’s where I go, still — to the page — to sort out that which fascinates, horrifies, titillates, amuses and compels me.

Have you, in the past, dealt with having your books banned or threatened to be banned?

The book banning fever that has taken up so much air space over the past couple of years is really the first time I’ve seen a coordinated effort to remove my work from public spaces and school collections. In the past, I have been told quietly by librarians and teachers that they love my work but won’t put some of my titles on their shelves because they’re not sure about the content being “appropriate” for teens, but it’s not until the coordinated efforts of groups like Moms for Liberty (a ridiculous misnomer) that I’ve seen widespread targeted attacks.

And now, several of your books are on the “challenge” list. Which ones and why?

I have 16 titles that have been banned or challenged — the second largest list of targeted books of any American author, according to PEN America. My job is to create more art, and giving too much space in my head to ignorant, bullying people who want to strip all children of access to a diverse, vibrant body of literature does not serve my art.

In general, though, I can tell you that the arguments against my young adult novels (the books that are most commonly challenged) include claims that they are pornographic, anti-Christian, support abortion and are pervasively vulgar. I shouldn’t need to say this, but my novels are none of these things. They explore and reflect the fascinating, complex, sometimes bloody, fraught, dangerous experiences and emotions of my own coming-of-age.

How did you first find out your books were being banned (or challenged)?

I hear about bannings in many ways: concerned parents and students have reached out to me through my website, through Twitter and Instagram to let me know what’s going on in their communities; a friend of mine who partners with PEN America to track the bannings sometimes gives me a heads-up. Very often, I get a Google alert about it when it makes it into the news.

I know that the things that I write can feel subversive and uncomfortable and unsettling and even gross. But that’s what writing is. It’s about wrestling with life, and life is all these things, too. These parents say they want to keep kids “innocent.” But that’s not true. What they want is to keep kids ignorant — ignorant about America’s history and racism, ignorant about violence towards cisgender and transgender women, ignorant about the LGBTQIA+ community, ignorant about their own bodies.

I don’t write books to teach lessons. I write to untangle that which confuses and compels me; I write to transform my own painful lived experiences into art; I write to celebrate being a human. So the bannings don’t stop me from working. They remind me that it’s my great privilege to have a voice, and they spur me to be even louder.

To learn more about Elana K. Arnold, visit elanakarnold.com.