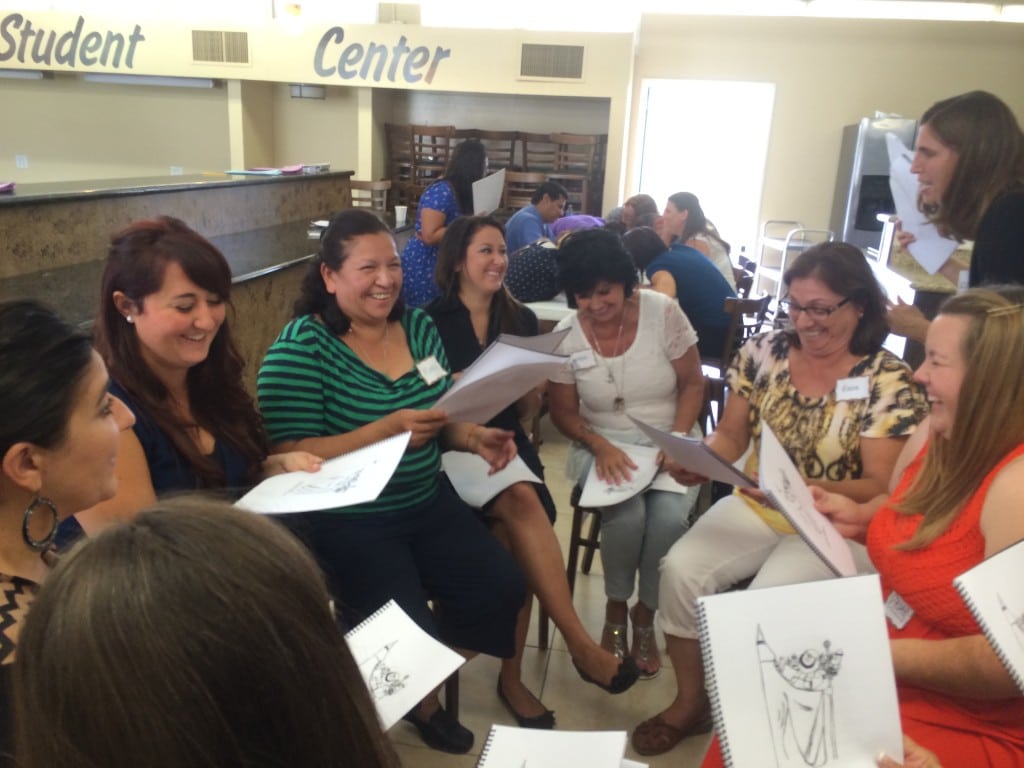

Exercises that simulate challenges faced by students with dyslexia help parents understand their frustration, but also give the chance to share a laugh or two.

I recently attended a parent workshop at the Frostig School in Pasadena, designed to give parents hands-on insight into what it’s like for students with special needs who struggle to read and write. Educational therapist Barbara Langeloh, M.A.,facilitated Experience Dyslexia – A Learning Disabilities Simulation. The goal was for participants to feel the frustrations our children experience daily, helping us deal more compassionately with them.

The six simulation activities, created by the International Dyslexia Association, are designed to educate anyone interested in the difficulties students with language learning disabilities face. The simulation was a helpful tool for any parent whose child is having a tough time academically.

Parents were split into six groups and given 10 minutes per station. My first task, “Write With Mirrors,” made me dizzy. I had to cover my writing hand, then look only at a mirror to trace and then write. My tracing of a star shape was pathetic and my number-writing skills (writing numbers that fit between two lines) were better, though still lacking. I spent too much time checking out what other members of my group members were doing – just like students do, only I was under no pressure to perform.

The exercise was followed by a debriefing where we compared notes and learned what challenges the exercise recreated. This station simulated visual and motor writing problems. We discussed our negative self-talk and how easily our self-esteem was quashed after being unable to successfully complete the exercise.

It often takes all the concentration parents can muster just to complete the exercises.

At “Write or Left,” we had to complete tasks neatly and quickly with our non-dominant hand. Despite being ambidextrous, I found this activity tiring. My left hand cramped and was unstable compared to my right hand, which has the proper muscle tone. One woman in my group rushed through this skill, certain she couldn’t do it. Another, feeling daunted, didn’t try. This station reproduced dysgraphia, which affects handwriting and fine motor skills.

Since my son has sensory processing disorder, I was fascinated by “Listen To Me,” a station mimicking what it’s like for children with auditory issues. Participants listened to a recording of a field trip and were asked to filter out irrelevant noise to hone in on what the teacher said. I was distracted by numerous sounds deliberately included. It seemed as though I heard the teacher speaking in a fog, and caught only every other word. That task helped me understand how much energy listening and concentrating take. No wonder kids often tune out and shut down or pretend they’re “getting it” and glide along. It’s hard!

Other stations provided invaluable insight into what students experience at school or in social settings when things become overwhelming, making seemingly simple tasks feel complex. At the “Learn to Read” station, which simulates ways that beginning readers struggle, even with my decoding skills, I still gave up. I could barely follow!

Maybe you’ve felt that your child with learning differences is just not trying hard enough at school. This simulation promises attendees an eye-opening exploration of what it’s like to walk in your children’s shoes. Find out how parents, parent support groups, schools and local organizations can organize an IDA simulation workshop by contacting the Los Angeles branch of IDA at www.dyslexiala.org or calling 818-506-8866.