Japanese Taiko performers entertain during a celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Japanese Speaking Parents Association of Children with Challenges. PHOTO COURTESY JSPACC

Visit the website of any of the county’s seven regional centers and a drop-down tab offers a list of more than 100 languages – from Afrikaans to Zulu – to help families connect with opportunities, information and services for those with disabilities. In a county as large and diverse as ours, this is hardly surprising.

But if you don’t speak English and are new to this country, who informs you that this website even exists? Or suppose what you need most is the wisdom of someone who has walked your path, comes from the same background and can provide a sympathetic ear?

Most people turn to family for comfort and guidance, and in many cultures, the belief that it takes a village to raise a child very much applies. If that child has a disability, however, things can be a bit different. Ignorance can be passed from one generation to the next as easily as wisdom and family members are not always welcoming and helpful.

Cultural Stigma

“Disability is a tough thing in a culture,” says Sonia Konialian-Aller, Ph.D., a founding member of the Armenian Autism Outreach Project (AAOP). For 11 years, this all-volunteer nonprofit has been working to raise awareness about autism in the Armenian community. “Often the word ‘disease’ is used to identify it and it has a stigma,” says Konialian-Aller. “It has components of shame and guilt.”

Within the Armenian community, for example, members of extended family often live together or near each other. It would not be uncommon in an Armenian household, Konialian-Aller says, for a grandparent to chalk up a child’s non-typical developmental behavior as “boys will be boys” or to pooh-pooh the idea that the child needs medical or psychological assessment. If a child is diagnosed with a disability such as autism spectrum disorder, older generations might encourage the parents to hide it.

“Obviously, for anybody, it’s an issue, because family relations are very important in the culture, and when something happens that not everybody understands and gets on the same page about, it creates an additional burden for the parents,” Konialian-Aller says.

Cristina Macasaet put distance between herself and her Filipino family for just this reason. “I had to move away from my family in Fullerton because my family was kind of coddling my children and not letting them spread their wings and learn how to adapt and develop their skills,” she says. “Sometimes I find my family is kind of holding back that training and education that has to happen.”

“In Filipino families, we’re passive. We tend to be followers,” Macasaet adds. “In terms of helping special-needs children, especially children with autism, in the Philippines, we would tend to keep them hidden, and that’s more because of shame. Here in American culture, parents kind of hear about things available out there and they need that little push to empower them to go ahead and ask questions. It’s better to do that instead of going into the stages of grief when you get a diagnosis.”

Help Speaking Up

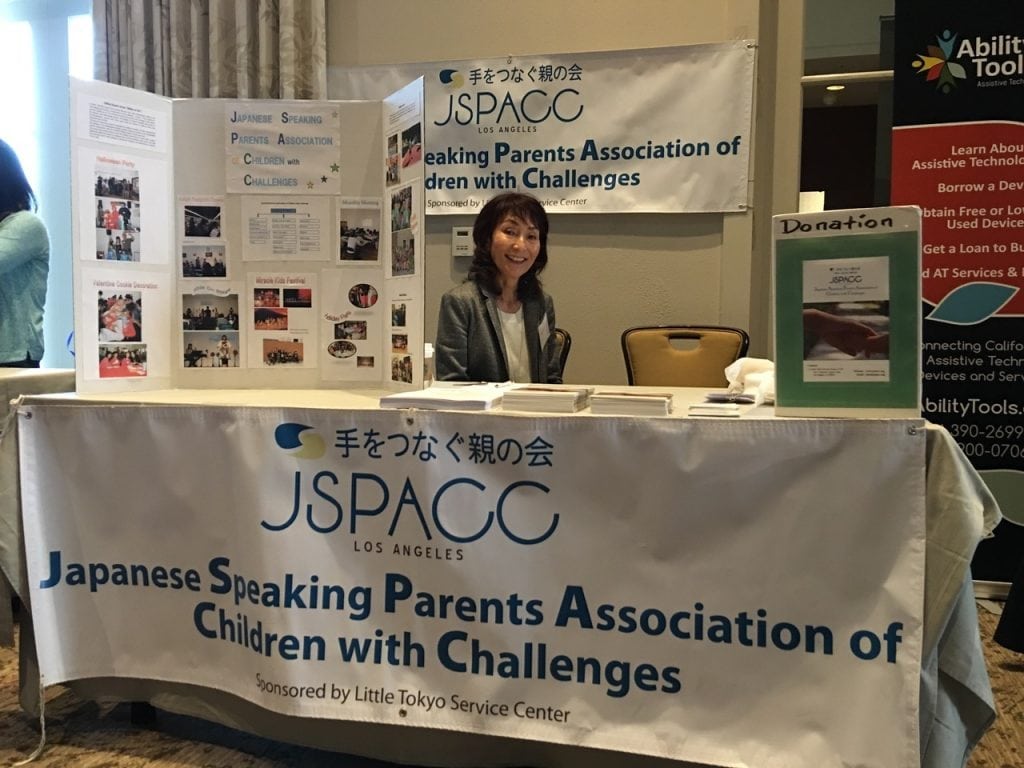

Members of the Japanese Speaking Parents Association of Children with Challenges participate in Nisei Week festivities. PHOTO COURTESY JSPACC

In a study published this year, UC Davis health economist J. Paul Leigh tracked the amount of money the California Department of Developmental Services spent on children with autism and found that white non-Hispanics get the most, followed closely by Asians. Hispanics were among the lowest funded ethnic groups. Data does not suggest that autism spectrum disorders occur more frequently within any specific ethnic group, but a parent’s ability or willingness to obtain service can vary greatly within cultures. Part of that, say parents, regional center administrators and advocates, can stem from a fear of speaking up and asking for help.

“Many families don’t speak English. That’s the real barrier,” says Francine Gomez who has an 18-year-old daughter with a disability. “Imagine when you have this fear, but you don’t speak English. How are you supposed to translate this feeling to another person and get the help you need? Parents are working two jobs and they have more than one kid. They don’t see what’s going on in the school and sometimes they forget about the kids with special needs.”

In areas with large minority concentrations, regional centers have taken steps to try to bridge the gap, hiring bilingual or multilingual resource specialists to do community outreach, serve as case managers and lead or organize parent support groups. Many of these specialists – including Macasaet, who now works at the San Gabriel/Pomona Regional Center – are also parents of children with disabilities. Macasaet frequently participates in SGPRC’s bi-monthly Filipino Parent Support Group.

Support Groups and Resources

Unable to find a support group for Japanese-speaking parents of children with disabilities, Mariko Magami founded her own. She is pictured here at the 2016 Asian and Pacific Islanders with Disabilities of California Statewide Conference. PHOTO COURTESY JSPACC

Support groups and other resources for families from Armenian, Filipino, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese and other backgrounds are offered through most regional centers or affiliated family resource centers. The network of resources for Spanish-speaking families dealing with disabilities is particularly extensive, with every L.A. County Resource Center offering at least one Spanish-speaking or bilingual support group.

Many of these organizations have been operating for more than 10 years, and most are staffed by parents of children with disabilities who have first-hand experience with the challenges faced by the people who reach out for help.

“Doctors know medicine. Lawyers know the law. We believe that nobody understands a parent except another parent who has walked in the same shoes,” says Elena Sanchez, a resource specialist who facilitates a number of Spanish-speaking support groups through the San Gabriel/Pomona Regional Center. “When we get together and share ideas and successes, we can empower ourselves. Something that might not be good for me might be good for another parent.”

Many regional centers have made cultural sensitivity an institutional mandate. “Families with different languages and cultural experiences may have difficulty being able to relate to the kinds of services we offer,” says Nancy Spiegel, director of information and development at Harbor Regional Center (HRC). “There’s a challenge to communicating with them about their child’s needs and what services might be available to meet those needs and how to access them.”

HRC recently created a group for Cambodian and Japanese speakers, and in collaboration with the University Center of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, has launched support groups for families that speak Spanish, Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese.

Community Connections

In addition to providing education and resources, many support organizations offer child care during support-group meetings and organize family-friendly events build community for parents and their children.

Because her daughter had been born prematurely, Heywot Bitew was already familiar with regional-center services when, some seven years later, her 18-month-old son was diagnosed with autism. Teri Mulugeta, Bitew’s case worker at Westside Regional Center in Culver City, recommended the WRC’s Ethiopian Support Group. Mulugeta, like Bitew, is Ethiopian.

Members of the Westside Regional Center’s support group for Ethiopian parents gather at Walk Now for Autism Speaks. PHOTO COURTESY WESTSIDE REGIONAL CENTER

Bitew says she resisted attending the support group for two years but has been a regular for the past six, often bringing her daughter and son, both of whom enjoy the social aspect. Bitew says she attends less for the information she will receive than for the feeling of community. As the group’s children get older and reach new developmental milestones, parents share common experiences. “There’s something about being in a room with people you may not know at the beginning, but you feel the connection, talking in a language you understand, talking about the challenges,” Bitew says. “Everybody has busy lives, but for the one or two hours that we’re there, we feel that bond.”

In 1987, Mariko Magami’s daughter Erika was born with a chromosomal defect that is similar to Down syndrome, as well as cerebral palsy and a congenital heart defect. The Tokyo-born Magami had been in the U.S. for only a short time and spoke little English. Someone put her in touch with the regional center and she was able to get Erika some in-home developmental therapy. Magami also attended parent-education seminars and a nine-month advocacy training session for parents of children with developmental disabilities.

“My English was still limited,” Magami recalls. “There would be 30 parents in the same room at the same hotel, and many times I lost what the speaker was talking about. But still, even that 20 percent of the lecture I could understand benefitted me and was a great education for me.”

With a year of education and training under her belt, Magami sought out a support group for Japanese-speaking parents of children with special needs. When she couldn’t find one, she created one – the Japanese Speaking Parents Association of Children with Challenges (JSPACC). More than 20 years later, the JSPACC puts out a newsletter, holds monthly meetings and brings in guest speakers.

Asked about cultural stigmas associated with having a child with disabilities, Magami agrees they exist but says that the feeling is less prevalent among younger generations of parents. She recalls bringing Erika, then a teenager, back to Japan to attend her father-in-law’s funeral. Erika’s paternal aunt and grandmother asked Magami to keep Erika away from a ceremonial event and from the funeral itself.

Magami reluctantly agreed, but her husband was furious, and the incident turned into a shouting match.

“My husband apologized that they would look at Erika that way, and told me he was ashamed of his mother and sister,” Magami says. “That’s OK. Everybody’s values are different. We live here. They live in Tokyo where the values and perceptions of special needs are completely different. After I got back, I shared that story with close friends and they understood my emotional problem and at the same time, they understood Japanese culture and the older generation stigma and negativity for people with special needs. They understand both.”

Evan Henerson is a local journalist and contributor to L.A. Parent.