Recently, a mom I know lamented that her formerly talkative son became silent when he turned 13. “He used to tell me about everything,” she said sadly. “Now it’s hard to get two words out of him and he does not share his life with us at all.” Her comment reminded me that I had suddenly felt panic 16 years ago when I was six months pregnant and realized I might have a boy. “How will I raise him?” I asked my husband. “What will I do when he’s a teenager?”

Recently, a mom I know lamented that her formerly talkative son became silent when he turned 13. “He used to tell me about everything,” she said sadly. “Now it’s hard to get two words out of him and he does not share his life with us at all.” Her comment reminded me that I had suddenly felt panic 16 years ago when I was six months pregnant and realized I might have a boy. “How will I raise him?” I asked my husband. “What will I do when he’s a teenager?”

Since I gave birth to a girl three months later, I didn’t have to grapple with the issues of parenting a son. My daughter and I have our own angst and she is less communicative at 15 than she was at 4, but she continues to share her life with me. My girlfriends with teen boys are dealing with other issues, not always knowing what their sons need from them. The boys often don’t understand when they need help or know how to ask for it. Instead, they turn inward and try to figure it all out on their own.

The teenage years are a physically and emotionally challenging time and can be especially difficult for boys, who are trying to find their place in society amidst pressure from parents and peers.

Figuring It All Out

“Yes, teen boys’ prefrontal cortexes are forming and they don’t have an understanding of consequences, so they can be reckless,” says Glendale-based family physician Esther Yoon, M.D. “Yes, the hormones are raging, hair is sprouting all over the place and they are in a really awkward life phase. Yes, they are brooding and sulking. But more importantly, they are trying to figure out what it means to be a man, what the criteria of being an adult are.”

When girls get their periods, Yoon says, they know they can bear children, that they have become women. Boys have a less concrete confirmation of manhood. “That’s why they might seek affirmation from their peers, whether by doing drugs, drinking alcohol or engaging in rough or violent play,” she says, adding boys don’t think they can share these feelings with their parents because it will make them anxious or angry.

While teen girls desire love from their parents, boys are seeking respect from family and peers. Yoon suggests that parents reassure their sons that they are not being judged. “We want them to learn to be gentle and sensitive but not destroy what is masculine about them,” she says. “We want to develop healthy males and honor them while also helping them learn how to communicate.”

Jennifer Macon, Humanities Magnet coordinator at Cleveland High School in Reseda, says that students talk a lot about the pressure to conform to stereotypical notions of masculinity and femininity, which generally starts in middle school. “For many boys, this equates to being quiet and stoic, feeling only as if they have permission to show ‘masculine’ emotions such as anger and aggression,” she says.

In 17 years of teaching, Macon says she has seen this pressure heightened as a result of social media. She adds that one of the few “safe” spaces for boys and men to express a fuller range of emotion is during sports play, where they exhibit jubilation and sadness, cry and hug in victory and defeat.

Nick Stein, a 17-year-old senior in the humanities magnet at Cleveland, expresses a similar view. “We’re not supposed to express how we feel,” he says. “We’re supposed to deal with it and move on. It affects the way men and boys react to each other and to people in general.”

Kari Keegan-Smith from L.A.’s West Adams neighborhood agrees. Long before her teenage daughters were born, she became the stepmom of three boys. “Boys are very linear. They only know the broader feelings,” she says. “The fine lines between emotions are lost on them, so they need to be taught.” Smith worked to honor her stepsons’ emotions and raise them to be well-rounded, compassionate and caring men while communicating with them directly and matter-of-factly on their level. “I never asked them at the end of a school day how school was,” she says. “I asked, ‘So how many guys picked their noses today?’ or something like that to get the conversation started.”

A Parenting Plan

Michelle East works to foster open communication with her sons, Caleb and Archer. PHOTO COURTESY MICHELLE EAST

Glendale-based therapist and yoga teacher Michelle East and her husband, musical director/composer David Ossman, also have a definite parenting plan for their boys. Seventeen-year-old Caleb studies music at the L.A. County High School for the Arts, and 11-year-old Archer is in elementary school. “I feel so much responsibility for bringing these guys a good foundation so that they know how to take care of themselves, so that they can be whole people,” says East. “We have an open communication with all subjects. They also have a whole group of people they can talk to about things. If they don’t want to talk to us, they can talk to Uncle Bill, Uncle Michael or Uncle Hutch.”

East’s top conversation tip: Go easy on the eye contact. “Confrontational eye contact can be threatening and put boys on the defensive,” she says. “Don’t challenge them with it. Some of our best conversations are side by side, walking or in the car.”

Psychologist Michael J. Bradley, Ed.D., author of “Yes, Your Teen is Crazy,” concurs. “Women like eye contact,” he says. “Men like to play ball together or go out for a drink. Boys are the same. The best way to talk to your son is walking, driving or laying next to him on the bed. That is non-threatening.” Bradley’s other teen conversation tips include:

- Time it right. Sleep-deprived mornings are lousy times for serious teen conversations. After school – and a day of criticism from teachers and coaches – might be even worse.

- Change the venue. If conversation isn’t going well at home, try the coffee shop or even cruising around town.

- Dose carefully. The best teen conversations are not one marathon, but 10 sprints.

- Less is more. After word seven, many teens tune out, so choose your words carefully.

- Control your volume. Yelling, demeaning and forceful speech simply fires up their brains. Save your breath.

- Don’t interrupt. Allow 10 seconds after your teen stops talking, then ask if he or she has more to say before you respond.

- Advise only if invited. Otherwise, just listen.

- Be ready to run. If the conversation goes south, disengage. Nothing good, and a lot bad, can happen once the raging starts.

Teens’ suggestions for their parents include being nonjudgmental, encouraging open communication but letting it take place at the teen’s initiation and pace and agreeing together on their parenting. “If both my parents could deal with my mistakes, I’d be less likely to make them again,” Stein says. “My parents are never on the same page. It creates a dynamic where you’re doing something that one parent is OK with, but the other isn’t. You’re setting yourself up for some bad stuff.”

The Role of Dads and Moms

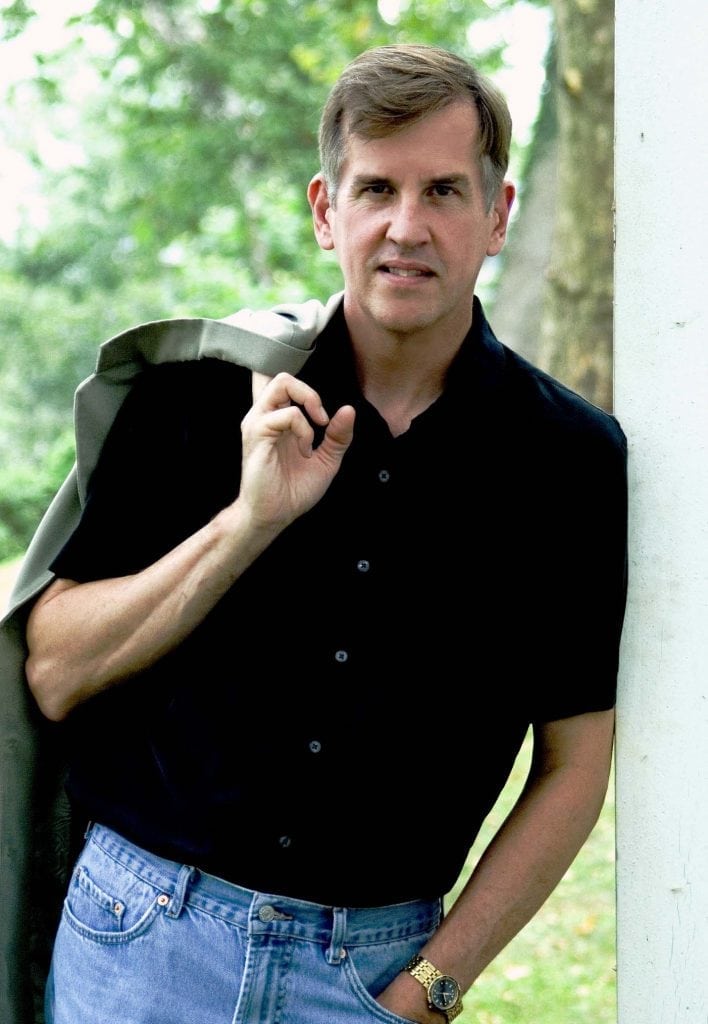

Psychologist and author Michael J. Bradley, Ph.D., advises talking to your teenage son while you are walking or driving together, so you don’t have to make eye contact. PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL BRADLEY

Eleven-year-old Mino Kon is just beginning the journey toward puberty. His mother, Los Feliz acupuncturist and Eastern medical practitioner Stacy Lauren-Kon, says he is a huge concern to her. “I worry that he will keep deep pain inside – the normal pain of a teenager but also that of having a [hyper] male role model in the house and an emotional female one,” she says. “How does he integrate both into himself?”

Kon believes it is essential to teach boys to embrace both male and female qualities and acknowledge that their fathers grew up in a different generation. She says boys must learn to look inward and process emotions while also respecting their fathers.

Dads have a big role to play in this regard, providing structure and creating bonding moments with their sons. “These are things that Dave is taking great care to teach the boys: how to shave, how to go on a date, how to create conversation,” East says of her husband. “They talk extensively and freely together.”

Yoon suggests that mothers need to understand male ideas of honor and respect and tailor their language accordingly. “Boys still need their moms, but they need them in a different way,” she says. “It may not be about hugs and cuddles anymore unless they ask for them, and using terms like ‘little man’ can be disrespectful to growing boys.” She recommends that mothers of boys read “Mother & Son: The Respect Effect” by Emerson Eggerichs, Ph.D.

In the end, showing that unconditional love, support and openness is a parent’s most valuable tool. “Point out the dichotomies and imperfections of life,” advises Kon. “Point out the reasons why it might be hard to talk. Say, ‘If you can feel free to communicate, let me know how I can help you, my love. This is what you were dealt. Women have overcome a lot and so must you, so you can have a voice and a rich emotional life.’”

Kaumudi Marathé is a Glendale-based writer and mom who frequently contributes to L.A. Parent.