Los Angeles is one of the world capitals of public art. Since what constitutes public art can be a matter of ambiguity — and even debate — for some clarity I turned to art historian Lucy Lippard, who has said that “the ‘public’ in public art can be read two ways — passive or active — as private art in public spaces or as art intended to be understood and enjoyed (or even made) by ‘the public.’”

Generally speaking, public art is a piece of art that lives in a public space. Some public art pieces are political, while others were crafted purely for aesthetic appreciation. At its best, public art is inspirational, educational and even delightful.

Murals and sculptures are the most obvious forms, but the world of public art can also include installations, fountains, wall treatments, benches, pergolas, skylights, stained-glass windows, sidewalk plaques and other collaborations between artists and architects. Every Los Angeles Metro station boasts site-specific public art pieces, for instance. And in the SoCal region, hundreds of public artworks have been commissioned for libraries, courthouses, fire stations, train stations, sports arenas and hospitals, as well as numerous standalone pieces.

My familiarity with public art started two decades ago when I began giving walking tours for Red Line Tours and the Downtown Art Walk between Downtown L.A.’s Historic Core, Little Tokyo, Los Angeles Central Library and Bunker Hill. There are nearly sculptures between Grand Park and the library alone. More recently, thanks to a new project called Grand Avenue Augmented, you can now encounter these sculptures in a new light on three blocks of Grand, from The Music Center to the U.S. Bank Tower, in a whole new dimension on your cell phone through QR codes that bring up animated sculptures, interactive holograms, virtual performances and immersive 360-degree environments created by more than 30 local artists.

As a professor, I have taken many of my students to see public art because it can be transformative. Local cultural critic and poet Jenise Miller told me that growing up next to Elliot Pinkney’s mural at the Mafundi Institute in Watts inspired her to study urban planning and become involved in community development work. I have heard my students say something similar after I took them to see murals painted by Judy Baca and Paul Botello.

In this roundup, you’ll find some of my favorite pieces of public art in SoCal. I don’t include places such as Watts Towers and Urban Light at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art because they are so well-known.

Armenian Genocide Memorial – Montebello

Located in Montebello, just south of the 60 freeway along Garfield Boulevard next to Bicknell Park and a golf course, the Armenian Genocide Memorial was built in 1968. Visited by thousands every year, especially on April 24, the annual remembrance day for the Armenian genocide, the sculpture stands over 75 feet high.

Designed by architect Hrant Agbabian, it consists of eight cement columns incorporating the cone-shaped steeples typical of Armenian churches. Montebello was the first Southern Californian Armenian enclave, and this site remains the oldest and largest American memorial dedicated to the Armenian genocide.

Four Arches – Downtown L.A.

This mobile by Alexander Calder was built in 1973 along Hope Street in Downtown L.A. between Third and Fourth streets next to the Bank of America Plaza. “Four Arches” is one of the most monumental pieces of public art in Southern California. Rising to 63 feet, the abstract red-orange-burgundy sculpture is made of carbon plate steel that looks like gracefully bent ribbons intersecting together in three-dimensional space.

Adjacent to a 52-story skyscraper, Calder’s masterpiece is breathtaking and almost eludes words in its stature. Calder is known for innovating sculpture with his invention of the mobile. He is also known for creating the first public work of art in the United States that was funded by the National Endowment of the Arts’ Art in Public Places program. Four Arches is iconic, playful and perfect for photographing.

Biddy Mason Park – Downtown L.A.

This pocket park in Downtown L.A. is directly south of the Bradbury Building in between Broadway and Spring streets and Third and Fourth streets. Designed by landscape architects Katherine Spitz and Pamela Burton, the park features one of the most poignant public art examples in L.A.: the artwork “Biddy Mason Time and Place.” This piece is an 80-foot-long poured concrete wall by artist Sheila Levrant de Bretteville. Biddy Mason was a 19th century Black woman who was born a slave but, after arriving to California in 1856, launched a legal battle for her freedom. She successfully won her freedom and became a businesswoman who owned the land on which Biddy Mason Park now stands.

Like a river, the wall installation captures the timeline of Mason’s life and is adorned with objects, text and images relevant to her life — agave leaves, wagon wheels and a midwife’s bag — and an early map of Los Angeles and Mason’s freedom papers. The wall concludes with “Los Angeles mourns and reveres Grandma Mason.”

California Scenario – Costa Mesa

Designed by Isamu Noguchi in 1982, this sculpture garden in Costa Mesa is a few blocks from the South Coast Plaza. Created to represent specific California geographical features, it incorporates indigenous plants and materials with six principal elements spanning the forest, desert, water sources and more.

Noguchi was an internationally acclaimed artist and considered one of the most esteemed landscape architects of the 20th century. California Scenario is one of America’s premier sculpture gardens and a hidden jewel one could easily miss because it sits between two office buildings. It is also less than two blocks south of a new architectural marvel: the Orange County Museum of Art.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles – Valley Village near North Hollywood

Coming in at nearly 2,800 feet, The Great Wall of Los Angeles mural is a 10,000-year people’s history of California — from the last ice age to the 1984 Olympics. Located along the Tujunga Wash between Oxnard and Burbank boulevards in the middle of the San Fernando Valley, it portrays images of Native Americans, Biddy Mason, Albert Einstein, Chinese railroad workers, the citrus industry and Rosie the Riveter.

Painted over the course of seven summers from 1976 to 1983, the mural, designed by Judith Baca, is going to be extended even further, thanks to a $5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The mural included assistance from more than 300 teenagers who helped Baca paint it through community programs. One of Baca’s favorite phrases is “Collaborate first, then paint.”

Pasadena Robinson Memorial – Pasadena

This memorial consists of two bronze portrait head sculptures — one of groundbreaking baseball player Jackie Robinson, the other of his Olympic medal-winning brother Mack Robinson. Ralph Helmick and John Outterbridge created these sculptures located in Pasadena’s Centennial Square just across from Pasadena City Hall.

The Robinsons grew up in Pasadena, so honoring them here is apropos. Jackie faces east, looking past City Hall and towards New York, where he broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Mack sculpture gazes directly at City Hall because he stayed in Pasadena and worked for the city. Though Mack was not as famous as Jackie, he won a silver medal in the 1936 Olympics. A Pasadena post office and stadium at Pasadena City College are also named after him. A closer look reveals that text and bas relief imagery are embedded in their hair, making reference to their many accomplishments in politics, sports and community service.

Sankofa Passage – Leimert Park

The Sankofa Passage is a community-initiated site along Degnan Boulevard in Leimert Park that features 16 bronze plaques with two names on each plaque. Essentially Leimert’s “Walk of Fame,” the project is intended to preserve, document and educate the public about the many Black artists and visionaries who made their mark in the Leimert Park/Crenshaw district.

Luminaries Horace Tapscott, Billy Higgins, Marla Gibbs, Clora Bryant, Eric Dolphy, Kamau Daaood, Paul Williams and 25 others are honored within a bronze pyramid bordered by the image of an enslaved person branding iron shapes enclosing their names, artistic fields and places and years of birth. Sankofa is an African principle and symbol from Ghana that asserts we must learn, respect and recognize the past so that the present and future generations can move forward. The Sankofa Passage honors the legacy of these greats and also offers inspiration to aspiring artists.

Lewis MacAdams Riverfront Park – Elysian Valley aka “Frogtown”

Formerly known as the Marsh Street River Park in Elysian Valley, this green space is now named after poet and environmental activist Lewis MacAdams, who co-founded the Friends of the Los Angeles River in 1985-86.

In 2018, a four-sided sculpture of MacAdams was installed in the park. Created by Eugene Daub, the rectangular-shaped sculpture stands at 6½ feet tall and is located near the park’s north end just south of the riverbed. The sculpture includes MacAdams’ face with his trademark hat and famous words, “If it’s Not Impossible, I’m Not Interested.” This quote fits because noone thought there was any possibility of restoring the Los Angeles River in the 1980s. The other three sides of the sculpture use MacAdams’ poetry. Though he passed in 2020, there’s now an annual Lewis MacAdams Prize for the best public art proposal along the Los Angeles River.

“We Believe in You” mural – East L.A.

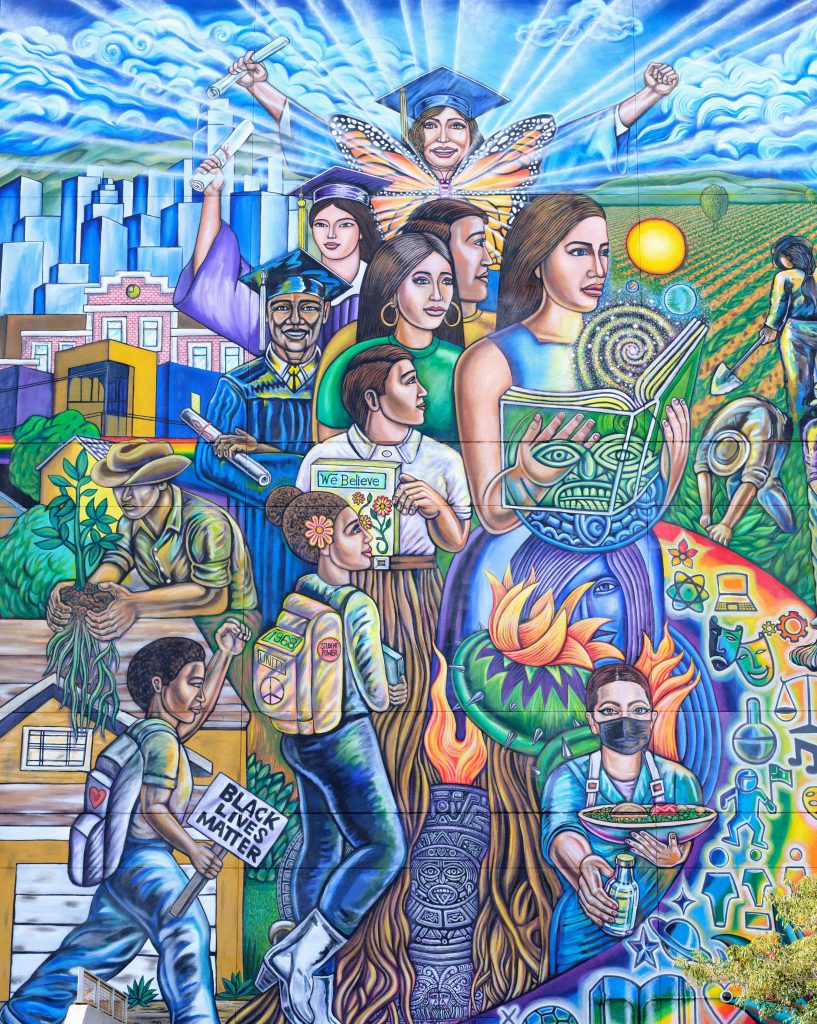

Los Angeles was once the mural capital of the world, and the epicenter spanned Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles. This monumental 50-by-50-foot mural on the front face of Esteban E. Torres High School in East Los Angeles was painted by lifelong Eastside artist Paul Botello.

The vivid mural shows students in higher stages of their education, climbing to various levels and culminating at the top with a young woman graduating, her diploma in hand. Rays of light emanate from her with an adjoining monarch butterfly. The metamorphosis of the butterfly represents how education changes a person — and how graduating is like a chrysalis becoming a butterfly. Botello brings multiple perspectives to the fore, spotlighting indigenous wisdom, the 1960s’ and 1970s’ Chicano movement and present movements such as Black Lives Matter. The many layers educate and inspire.

There are hundreds more examples of dynamic public art around Southern California. Keep your eyes open and explore!

Mike Sonksen is a Los Angeles dad, poet, professor and author of “Letters to My City.”