PHOTOS BY CASSANDRA LANE

Stepping into the new exhibit, “Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898-1971,” on view through April 9 at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, feels like slipping into a cave of long-lost treasures — many of them gems you didn’t even know existed.

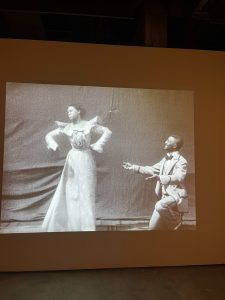

As soon as I entered the museum’s 11,000-square-foot Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Gallery, I was captivated by what film historians believe to be the first captured image of Black actors kissing on film: “Something Good — Negro Kiss,” created in 1898. I watched two elegantly dressed vaudeville performers, Saint Suttle and Gertie Brown, playfully lean into and push away from each other, then come back together multiple times to kiss. While this is a silent film, it speaks volumes. According to the Library of Congress, in 1898 alone at least 101 Black Americans were lynched across the U.S., and yet, “Something Good,” bursting with beauty and joy, is another archived reminder that tragedy is not the whole story of the Black American experience.

The exhibit makes an argument that film is not just fantasy; rather, it is an art form packed with historical significance, political power and a unique ability to shape the attitudes and perceptions of cultures all over the world. One of the many quotes running throughout the exhibit comes from William D. Foster, a pioneering filmmaker born in 1884, and his words support the exhibit’s thesis: “Nothing has done so much to awaken the race consciousness of the colored man in the United States as the motion picture. It has made him hungry to see himself as he has come to be.”

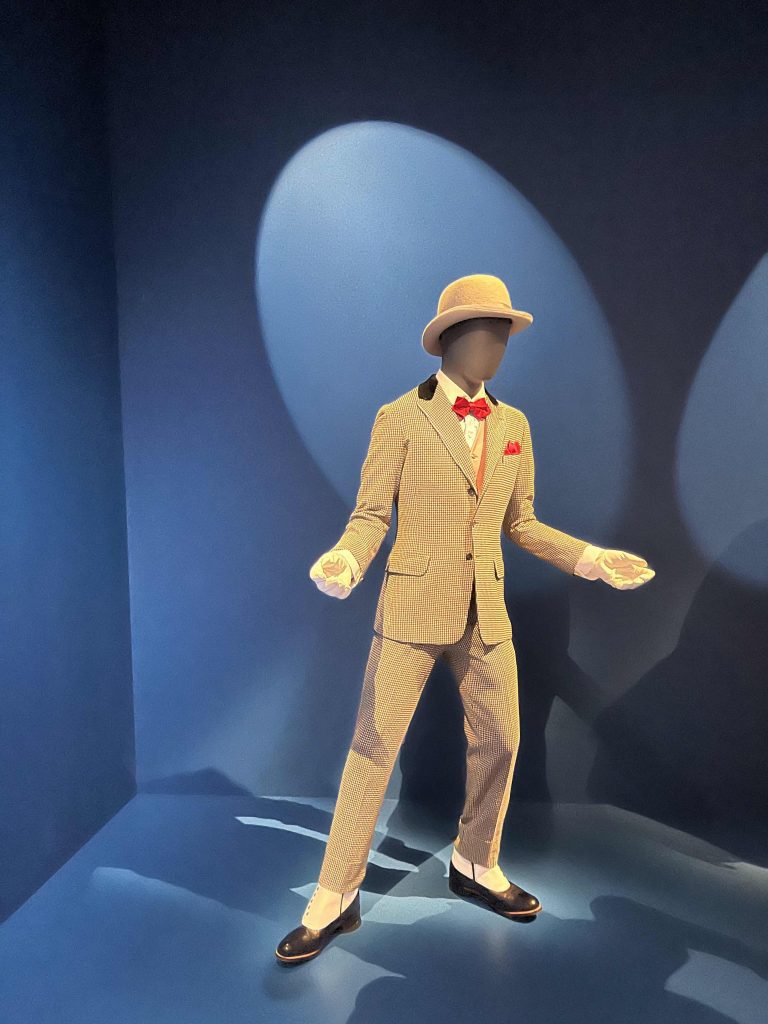

I wandered slowly through the exhibit, which stretches across seven galleries, gazing at film clips, large movie posters, costumes worn by Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr. and more, a 1920s camera, a Mills Panoram machine from the 1940s (in which we get to see Louis Armstrong blow his trumpet), a glass-enclosed Oscar (whose recipient was Sidney Poitier) and documentaries exploring the civil rights era and the Black Power Movement. The dance between how America was treating its Black citizens and how those citizens countered injustices through the power of storytelling is a running theme throughout the exhibit.

Aptly named, “Regeneration” is a project that has been in development — research, discovery, restoration, partnership — for nearly five years. The idea sprouted when Doris Berger, vice president of Curatorial Affairs, was conducting research in the museum’s Margaret Herrick Library and discovered posters for Black-cast movies such as “The Flying Ace,” a 1926 film. These “race films,” or films produced for Black audiences between the 1910s and 1940s, intrigued her. Berger serves as co-curator of “Regeneration” with Rhea L. Combs, director of Curatorial Affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, with additional curatorial support from the Academy Museum’s Raúl Guzmán, assistant curator, Manouchka Kelly Labouba and Emly Rauber Rodriguez, research assistants.

At a press conference to launch the exhibit, Combs, Berger and Academy Museum Director and President Jacqueline Stewart discussed the scope of the exhibit and how artifacts were “rescued from oblivion.” “Regeneration,” Combs and Berger write in the exhibition catalog, “is the first large-scale exhibition of its kind to examine the compellingly rich history of Black participation in American cinema, both within and outside the Hollywood studio system.”

Filmmakers Ava DuVernay and Charles Burnett, who both served as advisors for the project, said a project of this scale was long overdue.

Burnett, whose acclaimed films include “Killer of Sheep” (1978) and “To Sleep With Anger” (1994), said he wishes he had known about this deeper legacy of Black filmmakers when he was first starting out. “If I had known, I might have had a different motivation and approach to film,” he said. “I would have at least had a foundation instead of thinking that I was having to reinvent the wheel.”

After watching the famous clip of the tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers in “Stormy Weather” — the one in which they slide down stairs and land on the floor in splits — DuVernay said that scene “captures the essence” of what the exhibit celebrates: pure joy and immense talent. “This is an absolutely essential and quite extraordinary exhibition,” she says.

What the exhibit makes palpable, DuVernay said, is “the love these pioneering Black filmmakers had for their people, the love that Black audiences had for images of themselves and the love for film that we all share — and that goes for everyone in this room and beyond.

“And so, with their outstanding scholarship [Berger and Combs] illustrate in this exhibit a long-hidden fact: That we Black folks have always been present in American film right from the start,” DuVernay said. “Present not as caricatures and stereotypes, but as creators and producers and innovators and eager audiences.”

Luckily, the general public can take part in a library of films through screening program curated by guest film curator Maya Cade, creator and curator of Black Film Archive and a scholar in residence at the Library of Congress. The series kicked off Aug. 25 with the world premiere of a new restoration by the Academy Film Archive of the 1939 “lost” film “Reform School” starring Louise Beavers. Upcoming film showings include “No Way Out” and “Native Son” Sept. 9, “Odds Against Tomorrow” and “The World, The Flesh and The Devil” Sept. 10, “The Learning Tree” and “A Raisin in the Sun” Sept. 23 and more.

A new set of screenings will release later this year and in early 2023, including world premieres of newly restored films such as “Harlem on the Prairie” (1937) and “Mr. Washington Goes to Town” (1942).

In addition to the kaleidoscope of Black film history and artifacts, you’ll find contemporary visual works of art woven throughout the exhibit, including Kara Walker’s silhouette installation “The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven.”

To deepen its educational outreach, the museum has created a “Regeneration” curriculum guide that invites teachers and high school students to engage with the exhibition. In addition, The Regeneration Summit, a two-day celebration of Black cinema featuring artists, scholars and filmmakers in panels, workshops and activations through the museum, will take place Feb. 3-5.

For more information, visit regenerationblackcinema.org.

Cassandra Lane is Editor-in-Chief of L.A. Parent.