This summer, a group of California students between the ages of 14 and 17 gathered together to write and discuss poetry as part of the 2023 California State Summer School for the Arts program. These 11 artists felt so much passion for the literary work that they decided to create a safe space for other teen writers to showcase their work through a peer-writing group: The 309 Collective.

They young writers will host their first event this weekend with an open mic night open to the public. The collective meets up every Sunday for a Zoom meeting to write together, get feedback on what they are currently working on or have guest speakers.

Spearheading this movement is teen Bella Giammalvo, one of the visionary founders, emphasizing a collaborative spirit where every member plays a pivotal role. “We all want to publish our own work and support each other in our writing,” Giammalvo says.

Poet, author and Writ Large Press co-founder Chiwan Choi serves as the group’s advisor, supporting the students in any way they need, but makes a point to avoid hovering over the students’ endeavors. Choi, who is also a copy editor for L.A. Parent, speaks highly of his students. “My hope is that each of them publishes their own books,” he says. “I will be there to help in any way. The big exciting part is that you never know what teen will come to our open mic nights and become inspired to create a group at their school.”

This collective strives to help build strong communities of writers within L.A. beyond their individual educational institutions. Choi and Giammalvo both feel their virtual meetings are a perfect environment for teens to springboard their creative ideas individually and collectively.

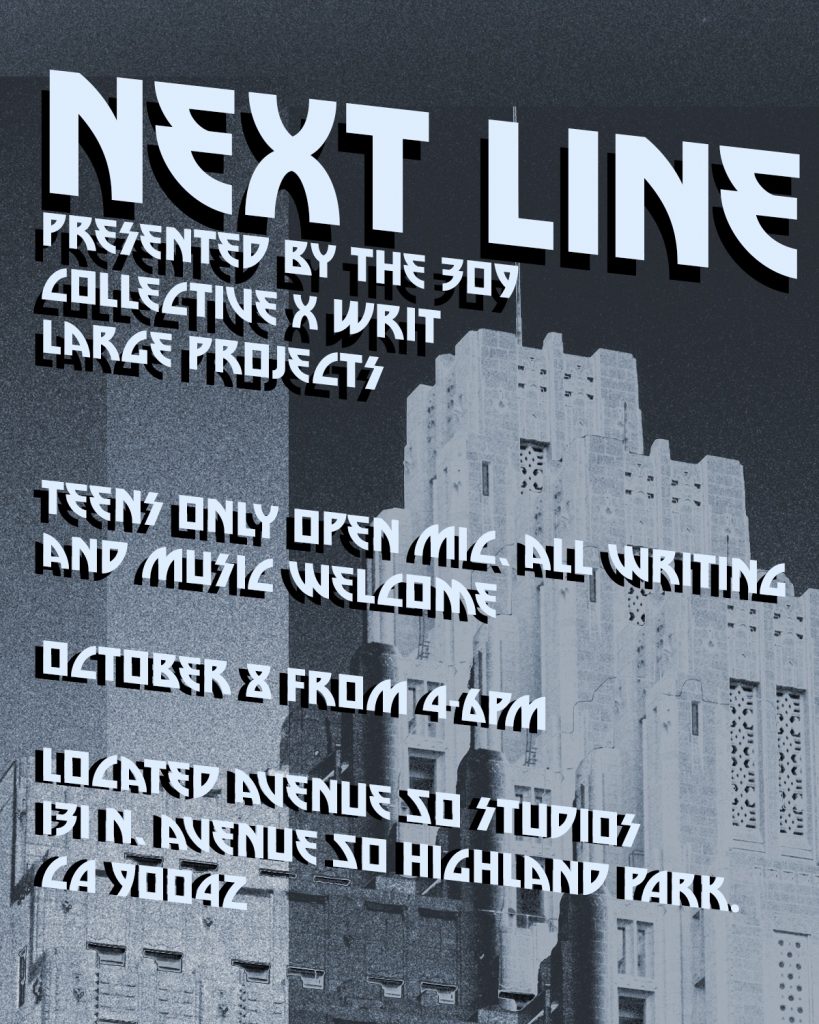

The 309 Collective’s first event, “Next Line,” an open mic for teen writers and musicians, will take place 4-6 p.m. Sunday, Oct. 8. The event will be held at Avenue 50 Studio 131 N. Avenue 50, Los Angeles.

For more information, visit the309collective.com/. The 309 Collective can be reached via email at the309collective@gmail.com or through social media @the309collective.